The surprise is not that Boeing lost commercial crew but that it finished at all

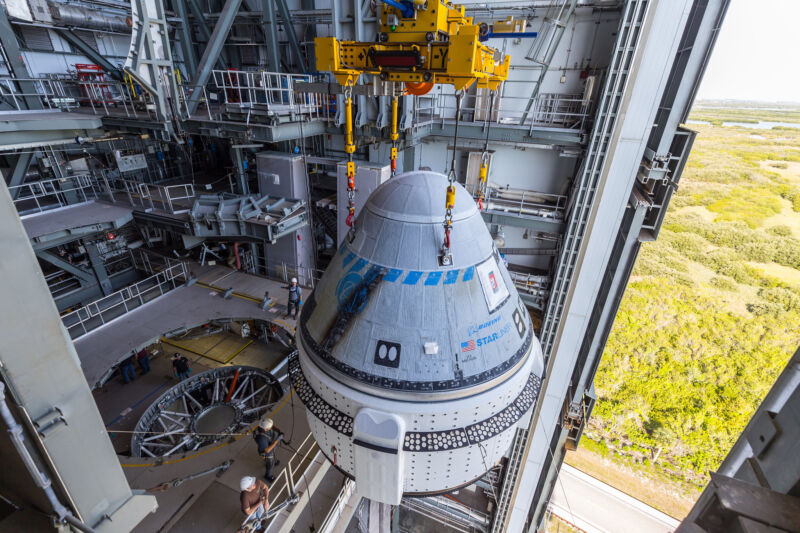

United Launch Alliance

NASA’s senior leaders in human spaceflight gathered for a momentous meeting at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, DC, almost exactly 10 years ago.

These were the people who, for decades, had developed and flown the Space Shuttle. They oversaw the construction of the International Space Station. Now, with the shuttle’s retirement, these princely figures in the human spaceflight community were tasked with selecting a replacement vehicle to send astronauts to the orbiting laboratory.

Boeing was the easy favorite. The majority of engineers and other participants in the meeting argued that Boeing alone should win a contract worth billions of dollars to develop a crew capsule. Only toward the end did a few voices speak up in favor of a second contender, SpaceX. At the meeting’s conclusion, NASA’s chief of human spaceflight at the time, William Gerstenmaier, decided to hold off on making a final decision.

A few months later, NASA publicly announced its choice. Boeing would receive $4.2 billion to develop a “commercial crew” transportation system, and SpaceX would get $2.6 billion. It was not a total victory for Boeing, which had lobbied hard to win all of the funding. But the company still walked away with nearly two-thirds of the money and the widespread presumption that it would easily beat SpaceX to the space station.

The sense of triumph would prove to be fleeting. Boeing decisively lost the commercial crew space race, and it proved to be a very costly affair.

With Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft finally due to take flight this week with astronauts on board, we know the extent of the loss, both in time and money. Dragon first carried people to the space station nearly four years ago. In that span, the Crew Dragon vehicle has flown thirteen public and private missions to orbit. Because of this success, Dragon will end up flying 14 operational missions to the station for NASA, earning a tidy fee each time, compared to just six for Starliner. Through last year, Boeing has taken $1.5 billion in charges due to delays and overruns with its spacecraft development.

So what happened? How did Boeing, the gold standard in human spaceflight for decades, fall so far behind on crew? This story, based largely on interviews with unnamed current and former employees of Boeing and contractors who worked on Starliner, attempts to provide some answers.

The early days

When the contracts were awarded, SpaceX had the benefit of working with NASA to develop a cargo variant of Dragon, which by 2014 was flying regular missions to the space station. But the company had no experience with human spaceflight. Boeing, by contrast, had decades of spaceflight experience, but it had to start from scratch with Starliner.

Each faced a deeper cultural challenge. A decade ago, SpaceX was deep into several major projects, including developing a new version of the Falcon 9 rocket, flying more frequently, experimenting with landing and reuse, and doing cargo supply missions. This new contract meant more money but a lot more work. A NASA engineer who worked closely with SpaceX and Boeing in this time frame recalls visiting SpaceX and the atmosphere being something like a frenzied graduate school, where all of the employees were being pulled in different directions. Getting engineers to focus on Crew Dragon was difficult.

But at least SpaceX was in its natural environment. Boeing’s space division had never won a large fixed-price contract. Its leaders were used to operating in a cost-plus environment, in which Boeing could bill the government for all of its expenses and earn a fee. Cost overruns and delays were not the company’s problem—they were NASA’s. Now Boeing had to deliver a flyable spacecraft for a firm, fixed price.

Boeing struggled to adjust to this environment. Regarding complicated space projects, Boeing was used to spending other people’s money. Now, every penny spent on Starliner meant one less penny in profit (or, ultimately, greater losses). This meant that Boeing allocated fewer resources to Starliner than it needed to thrive.

“The difference between the two company’s cultures, design philosophies, and decision-making structures allowed SpaceX to excel in a fixed-price environment, where Boeing stumbled, even after receiving significantly more funding,” said Lori Garver in an interview. She was deputy administrator of NASA from 2009 to 2013 during the formative years of the commercial crew program and is the author of Escaping Gravity.

So Boeing faced financial pressure from the beginning. At the same time, it was confronting major technical challenges. Building a human spacecraft is very difficult. Some of the biggest hurdles would be flight software and propulsion.